What follows is an essay of growth—both personal and theological. I come from deeply entrenched Evangelical roots, and for most of my life, I held a grim view of creeds and confessions and a high view of Scripture. When I began to deconstruct my faith, I added theological statements to my mental list of anathema documents. Rejecting anything that smelled of hierarchy, tradition, or theological control felt liberating. But in hindsight, that rejection was not a departure from my Evangelicalism—it was the logical extension of it.

If I claimed to be “Bible-based,” then no secondary document—be it creed, confession, or theological statement—ought to inform me. That was the bus route I had inherited, and I followed it all the way to deconstruction junction.

For a time, I let that stand.

Eventually, however, I let go of “faith” as the primary unifying principle of Christianity and gave love its turn to shape what comes next. In doing so, I stopped centering belief in the Christian life. Love demanded my full attention. What we believe—how we define our convictions—faded quietly into the background.

This essay is my return to that question, but on very different terms. I’m not attempting to recenter faith in opposition to love, but to explore what it means to believe because we love, and to find hope where our inherited systems have failed. It is a reflection on creeds, institutions, and the radical unity we look for in all the wrong places.

You’ll notice the voice of this essay balances academic rigor with public accessibility. That’s intentional. I’ve chosen to write in a way that a former version of myself—steeped in certainty, wary of tradition, suspicious of institutions—might have heard and understood. Theological reflection, after all, is not only for the academy; it’s for the living, breathing people of God. If love truly leads, then even our most studied thoughts must speak in the language of invitation.

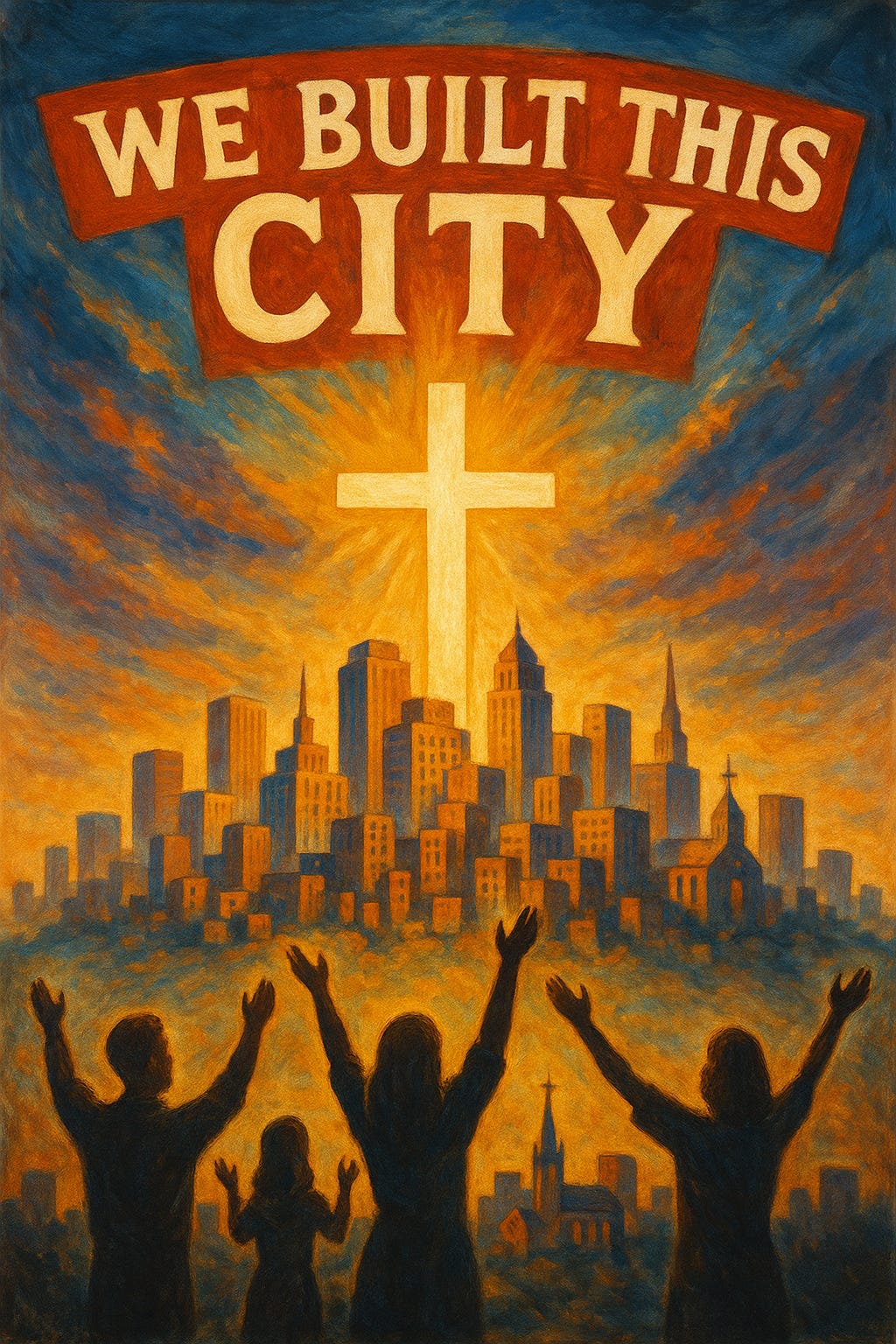

We Built this City

On Creeds, Control and the Collapse of Christian Institutions

By Daniel L. Bacon

The history of Christian thought is marked by creeds and theological formulations—documents such as the Apostles' Creed, the Nicene Creed, and the Westminster Confession. These have served as anchors of orthodoxy across denominations, but their capacity to unify the church in lived practice has proven limited. While many institutions claim them as foundational, doing so has not rendered them righteous by association. The truths these documents contain—though genuine—are not so true that they can redeem whatever form they inhabit.

I extend this critique to the Ten Commandments and broader efforts to reinsert Christian principles into civic spaces—such as the recent Texas Senate Bill, mirroring similar bills in other states.

Kurt Vonnegut, in A Man Without a Country (2005), lamented this selective public religiosity:

“For some reason, the most vocal Christians among us never mention the Beatitudes (Matthew 5)... That's Moses, not Jesus... 'Blessed are the merciful' in a courtroom? 'Blessed are the peacemakers' in the Pentagon? Give me a break.”

If what I’m saying holds true, then it applies equally to the Sermon on the Mount and the Ten Commandments. Neither law nor gospel can be reduced to plaques on a wall. Righteousness cannot be enshrined—it must be embodied.

This is not a rejection of the Ten Commandments, the Beatitudes, or the creeds. Nor is it a call to theological minimalism. It is a critique of our tendency to idolize frameworks—even biblical ones. We often hold creeds as antidotes to disunity, but it is not creeds that unify—it is love. Truth alone does not bind us, because truth holds no shape. Truth is lived, not merely confessed.

This departs from much Evangelical thought, where "the gospel is a message that must be shared" and the rejection of "actions speak louder than words" remains common. But does the gospel remain the gospel in any form, or is it proven by human lives?

We've misinterpreted our own metaphors. The instruction to bind God's law on our hands and foreheads (Deut. 6:8) was never meant to outsource faith to artifacts. Yet we construct monuments, slogans, and public declarations to carry the weight of obedience. A monument becomes a way to put God's law "out there" rather than live it "in here." We expect stone to carry righteousness when that burden was always ours.

In this way, our frameworks become Christian idols—not because they are false, but because we treat them as ends rather than means, as possessions rather than revelations. Like Israel with the bronze serpent (2 Kings 18:4), what began as a gift becomes a shrine. We idolize the Ten Commandments, the Beatitudes, even the Gospel—not out of rebellion, but out of misguided reverence. We want the fire without getting burned. We want godliness without its disruptive power.

But the gospel cannot be domesticated. It cannot be mounted, framed, or etched in stone. It is not English words or stained glass or constitutional amendments. It is fire. It is breath. It is life. If there is mercy in a courtroom, it must be human mercy. If there is peace in the Pentagon, it must come from those willing to lay down their lives, not cover fire.

To worship God rightly is to resist the urge to idolize the framework and instead embody the truth it points to. Creation already speaks this truth in every tree, storm, and smile. The gospel is not absent from the dance of creation, we just forget what it looks and sounds like until it bites us on the nose.

Back on the Bandwagon

I now turn to the Apostles' Creed, the Nicene Creed, and the Westminster Confession for clarity and focus. Though different in origin and emphasis, each became a touchstone of orthodoxy within its tradition.

While many Evangelicals affirm Scripture’s authority, their relationship to historic creeds is often marked by quiet resistance. These documents are respected in name but sidelined in practice. This reflects a deeper tension: a Bible-based tradition uneasy with shared theological language that predates its own expressions.

In many revivalist and non-denominational settings, we’ve shifted from confessional continuity toward individualized expressions of faith. Freshly written statements replace historical creeds—dynamic, but often less accountable. This mistrust of institutions and pursuit of relevance also leads to fragmentation and redundancy. We rewrite the same things, again and again, trying to capture unity in words rather than in relationship.

A theological crisis arises—gender, race, sexuality—and a new statement is drafted. It becomes a boundary marker. In this way, the church weaponizes theology. What was meant to unify becomes a tool of exclusion. This is not new. Even while the Nicene Creed stood unchallenged, churches sanctioned crusades, inquisitions, and slavery. The fault is not in the creeds, but in how we use them to control rather than guide in love.

We might say, “Let’s start fresh!” But institutionalization doesn’t fade easily. Many convictions are stained by complicity in injustice. Traditions—while profound—have often served as gatekeepers more than shepherds. The “Billy Graham Rule,” though intended to protect integrity, reinforces exclusion by equating proximity to women with moral risk. Gendered categories like “Men of God” and “Women of God” have functioned to marginalize.

This logic is not new either. From the Southern Baptist defense of slavery (1845) to the resegregation of Pentecostal movements post-Azusa, to today's debates over LGBTQ+ inclusion, we see the same exclusionary reflex. Creeds are often silent, but traditions fill in the blanks—appealing to the flesh, which Scripture warns against (2 Corinthians 5:16).

These failures aren’t unique to creeds or denominations. They arise from how we preserve power. When Christian leaders fall, institutions respond by tightening boundaries—more rules, more fences. Then, selectively, we make exceptions. This patchwork becomes our institutional life: a quilt sewn with fear and selective grace.

Such institutions don’t express a gospel-shaped community. They resemble preservation rafts—floating remnants of our attempts to live the Christian life by human systems. When Christ tore the veil (Matthew 27:51), He abolished the boundary between God and humanity, and among humans themselves. The Spirit was poured out on all flesh (Acts 2:17). To rebuild that veil with pedigree, education, or doctrinal conformity is to work against Christ. We do not undo His work, but we do burden others with a yoke they were never meant to bear (Galatians 5:1).

The torn veil is like the uncut stones used in altars (Exodus 20:25). It is not polished, not institutional. It is God's decisive act—a warning against mending what He has torn. Our systems of inclusion, exclusion, certification, and restoration are a form of spiritual tailoring. They try to fix what God deliberately left jagged.

So what is our alternative? If unity cannot be found in truth—because truth does not bind but rather frees (John 8:32)—then what remains is love. Not sentimentality, but the deepest truth of all: that love is. It is everything that exists. To be is to have been loved by God. To love is to acknowledge the existence of others and to behave only according to what is. Faith, then, is to trust with certainty that what is said will come to pass, even if unseen in this life.

In this light, the purpose of theological formulations shifts entirely. They are not badges, boundaries, or litmus tests. They are invitations—open hands reaching through history, attempting to name something of the love that holds us. When they cease to serve that purpose, they become hollow. When they are used to divide rather than to invite, to constrain rather than to liberate, they become enemies of the very gospel they claim to guard.

And so, this essay is not a rejection of creeds, confessions, or theological clarity. It is a call to recover their truest function: not as gatekeepers of orthodoxy, but as poetic witness to the reality of God’s love poured out on all flesh. The creeds may never have been meant to control us. But the way we’ve used them has caused harm. We cannot pretend otherwise.

To return to the creeds now is not to place them on a pedestal, but to ask whether they can still speak—if not with authority, then with honesty. Not as walls, but as windows.

What we need is not a new theology, but a new posture toward theology—a posture shaped not by fear of heresy but by a hunger for wholeness. The work of the Spirit is not the construction of better walls but the burning away of everything that stands in the way of love. If the words of our faith do not help us love better, they are just noise.

So here I am, once again, looking at these old words—“I believe…”—but now with eyes trained by love, not certainty. I no longer seek agreement as proof of righteousness. I seek relationship. I seek the kind of belief that grows from love, that makes room for doubt, that honors the jagged edges of the torn veil.

I believe—not because the creed tells me to, but because love compels me.

I believe—not in spite of my deconstruction, but because it cleared the ground for something truer.

I believe—not to earn belonging, but to name what love has already made true.

Creeds cannot hold the fire. But they can remind us where it once burned. They can be kindling. And if they spark the curios light of the gospel in our hearts full of childish faith and wonder, then that is enough.